The table of content

Introduction: Higher Education in the Digital Era

Universities today promote their educational services primarily through the internet. A university’s official website has become its digital calling card—representing it not only nationally but also internationally. More than a static page, a website is a platform where institutions share updates, highlight achievements, foster informal communication, and keep in touch with students, faculty, and stakeholders. It also showcases competitive advantages and supports the learning process.

Research confirms that these websites are the main source of information for prospective students choosing their future field of study and institution. The shift became even more visible during the pandemic: when much of social and economic life moved from offline spaces to online platforms, universities had to quickly adapt to meet new expectations.

For higher education institutions, this adaptation has not always been simple. Limited resources and a lack of transparency in information management have slowed the development of their online presence. Distance learning reform in Ukraine, for example, exposed the consequences of these shortcomings. The effectiveness of an institution’s website now plays a central role in how accessible and usable its digital services appear—yet convenience is often evaluated subjectively, making it difficult to measure with precision.

Usability in Higher Education Websites

The usability of university websites has been a subject of study for more than two decades. Specialists consistently agree that a website’s quality directly influences how well an institution can serve students, faculty, and stakeholders. A university’s digital presence is no longer just a communication channel—it has become the front door to the institution itself, shaping first impressions, building trust, and even influencing enrollment decisions.

Yet, the concept of “usability” remains elusive. What feels intuitive to one user might appear confusing to another. Factors such as age, cultural background, digital literacy, and prior online experience all shape how individuals judge whether a website is easy to use. This diversity of perspectives explains why researchers have proposed such a wide range of features, parameters, and evaluation frameworks. For some, usability is about navigation and accessibility. For others, it is tied to content quality, design aesthetics, or technical reliability.

Methodologies for studying usability are equally varied. Traditional approaches include sociological surveys, expert reviews, and cognitive testing. More advanced methods now integrate discourse analysis, eye-tracking, regression models, and even artificial intelligence. Tools like AWUSA and ANFIS have introduced structured, algorithmic ways to analyze website performance, allowing researchers to move beyond purely subjective judgments.

The urgency of this work has only grown in the digital age. Distance learning, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, exposed the critical role of university websites. For many students, a website was no longer an optional resource but the primary medium for lectures, materials, and communication. Institutions with well-designed, user-friendly sites were able to maintain continuity and engagement. Those with outdated or poorly structured platforms faced disruptions, frustration, and declining student satisfaction.

Despite decades of research, fundamental challenges remain unresolved. The subjective nature of usability resists universal definition. What works in one cultural or institutional context may fail in another. This lack of standardization often leaves universities unsure of how to prioritize improvements. As a result, many institutions continue to struggle, offering digital environments that meet technical requirements but fall short of delivering seamless and supportive user experiences.

In the future, progress will depend on bridging this gap between subjective user perceptions and measurable, objective criteria. Without such alignment, higher education risks lagging behind in digital transformation, leaving students and faculty with tools that frustrate rather than empower.

Results: What Makes a Higher Education Website Usable

As competition intensifies among universities to attract and retain students, expectations for their digital presence—particularly their websites—have risen dramatically. A modern university website is no longer just an online brochure; it is the primary gateway through which potential applicants, current students, faculty, and external stakeholders interact with the institution. Stakeholders expect platforms that are not only informative but also efficient, interactive, and visually accessible. In this environment, usability—the convenience and ease with which a website can be used—has become a decisive factor shaping user experience and, ultimately, institutional reputation.

According to the International Standard ISO 9241-11, usability is defined as the degree to which a product can be used effectively, efficiently, and with satisfaction to achieve a goal. This definition underscores that usability is not only about technical functionality but also about the quality of the experience. Experts such as Jakob Nielsen emphasize that usability goes beyond precise coding or design details; it involves protecting user rights, ensuring clarity, and maintaining simplicity. The ultimate goal is to create a system that any user—even those without prior training—can navigate with confidence and comfort.

Researchers and practitioners have identified multiple dimensions of usability. Nielsen’s framework highlights five fundamental components:

- Learnability – how quickly new users can become comfortable navigating the site.

- Efficiency – the speed and ease with which familiar users complete tasks.

- Memorability – how easily users can return to the site after a break and resume their tasks.

- Error tolerance – how well the site prevents mistakes and enables users to recover from them.

- Satisfaction – the overall sense of enjoyment and comfort when using the site.

Complementary studies extend these criteria, adding aspects such as page speed, interactivity, inclusivity, and accessibility. Taken together, these elements determine whether a university website feels seamless and supportive—or confusing and frustrating.

A distinctive characteristic of higher education websites is their non-commercial orientation. Unlike e-commerce platforms, their mission is not to sell products but to inform, connect, and support a wide range of users. This makes thoughtful design and information architecture especially important. Clear menus, logical navigation, functional links, and well-organized layouts help ensure that stakeholders—from prospective students to faculty members—can find what they need quickly and without unnecessary obstacles.

Recent research also stresses the importance of continuous internal monitoring. Usability is not a one-time achievement but an ongoing process. Institutions must regularly evaluate whether their websites keep pace with evolving expectations. This includes ensuring intuitive navigation, reliable search functions, and practical tools such as calendars, archives, registration systems, and interactive forms. Websites that fail to update or adapt risk alienating users and weakening institutional credibility.

Beyond these essentials, scholars have identified detailed usability standards specific to educational portals. These include readability of fonts, balanced distribution of text and visuals, correct rendering of multimedia, smooth registration processes, and easily visible “entry” and “return” points. Together, such elements form the invisible scaffolding of user experience. When they function well, users hardly notice them; when they fail, the entire site feels cumbersome.

Ultimately, usability is about more than convenience—it reflects the institution’s commitment to accessibility, transparency, and user-centered service. A usable website signals respect for its audience, making visitors feel supported and valued. In a competitive educational landscape, this intangible impression can make the difference between an institution that thrives and one that falls behind.

Modeling Usability with Fuzzy Logic

To evaluate website usability, it is important to consider the perspectives of stakeholders—students and applicants who actually use these platforms. In one study, a survey of 1170 participants showed that nearly 70 percent of respondents choose an institution for training based on the website. This demonstrates how strongly usability influences decision-making, even if the evaluation criteria are often subjective.

Because usability is partly subjective and not easily measured with precision, fuzzy logic is applied. Fuzzy logic is a mathematical approach designed to handle vague, qualitative factors and convert them into structured models. This method allows researchers to quantify aspects of usability that otherwise resist traditional measurement.

Stakeholders identified several key criteria for website usability. These criteria became the input parameters of the fuzzy logic model:

- Loading speed

- Convenience

- Efficiency

- Relevance

- Accessibility

- Interactivity

- Cross-browser compatibility

- Lack of forced content

- Attractive design

- Satisfaction

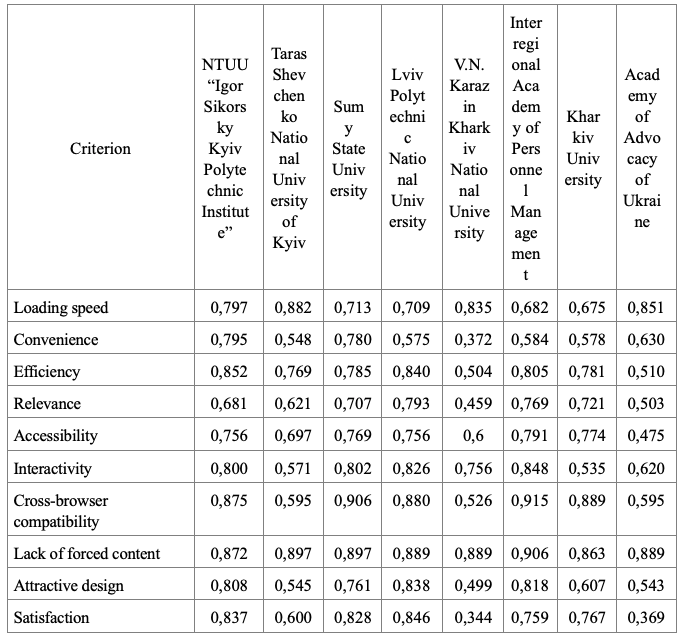

The model measures the relative weight of each criterion by comparing the obtained score with the maximum possible score. Preliminary calculations produced normalized indicators for a sample of higher education institutions.

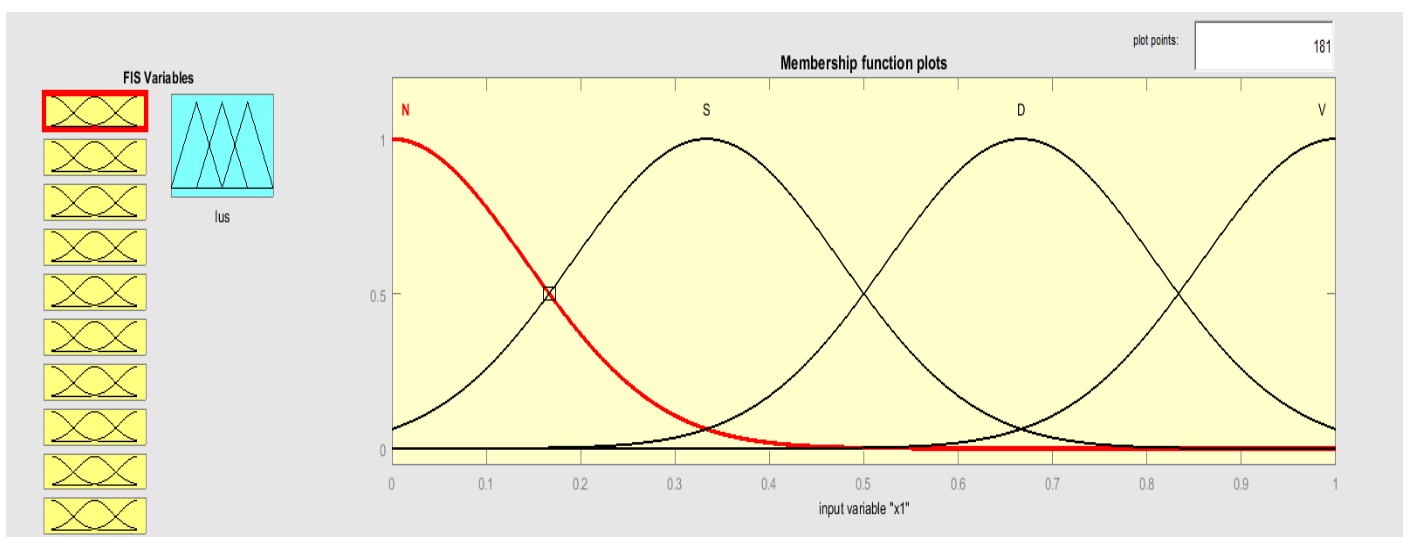

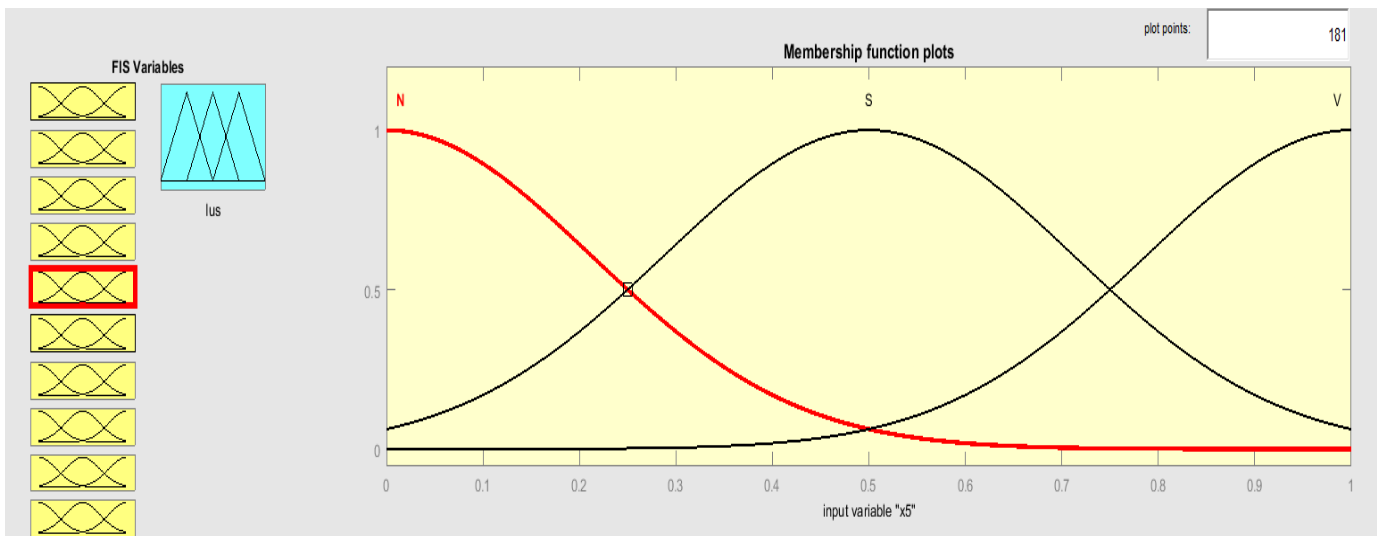

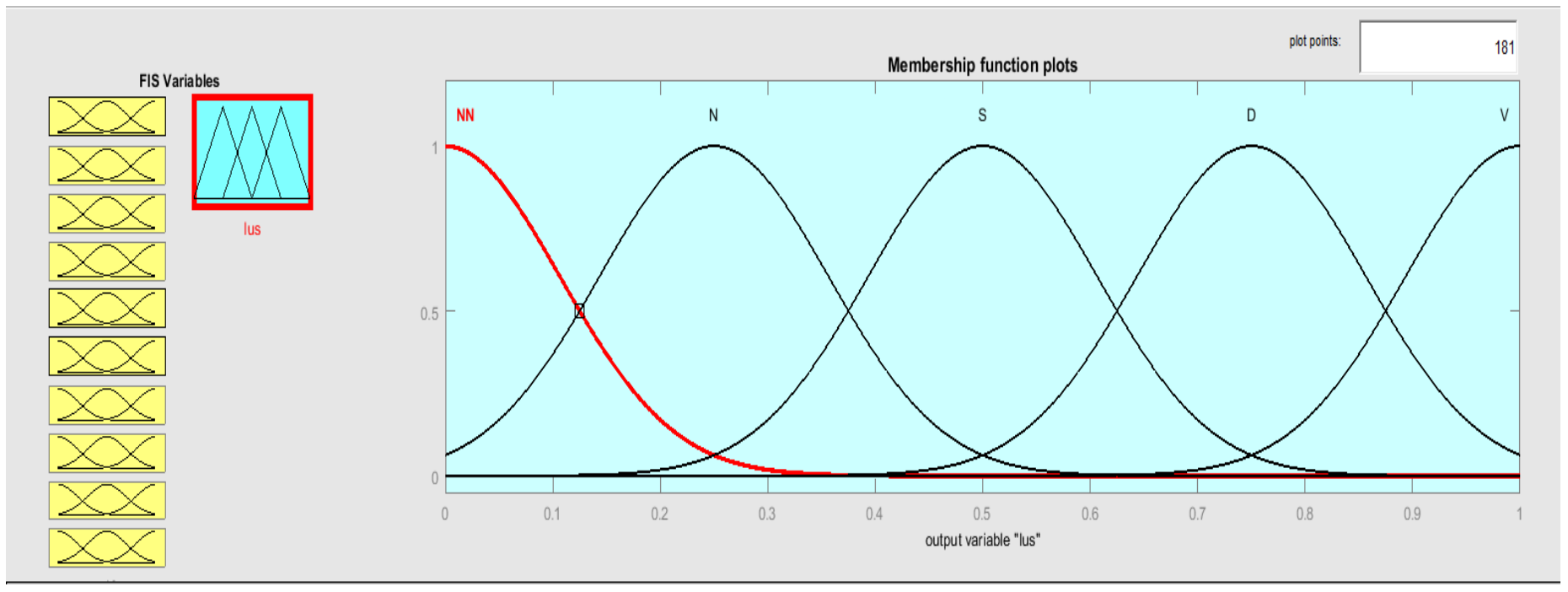

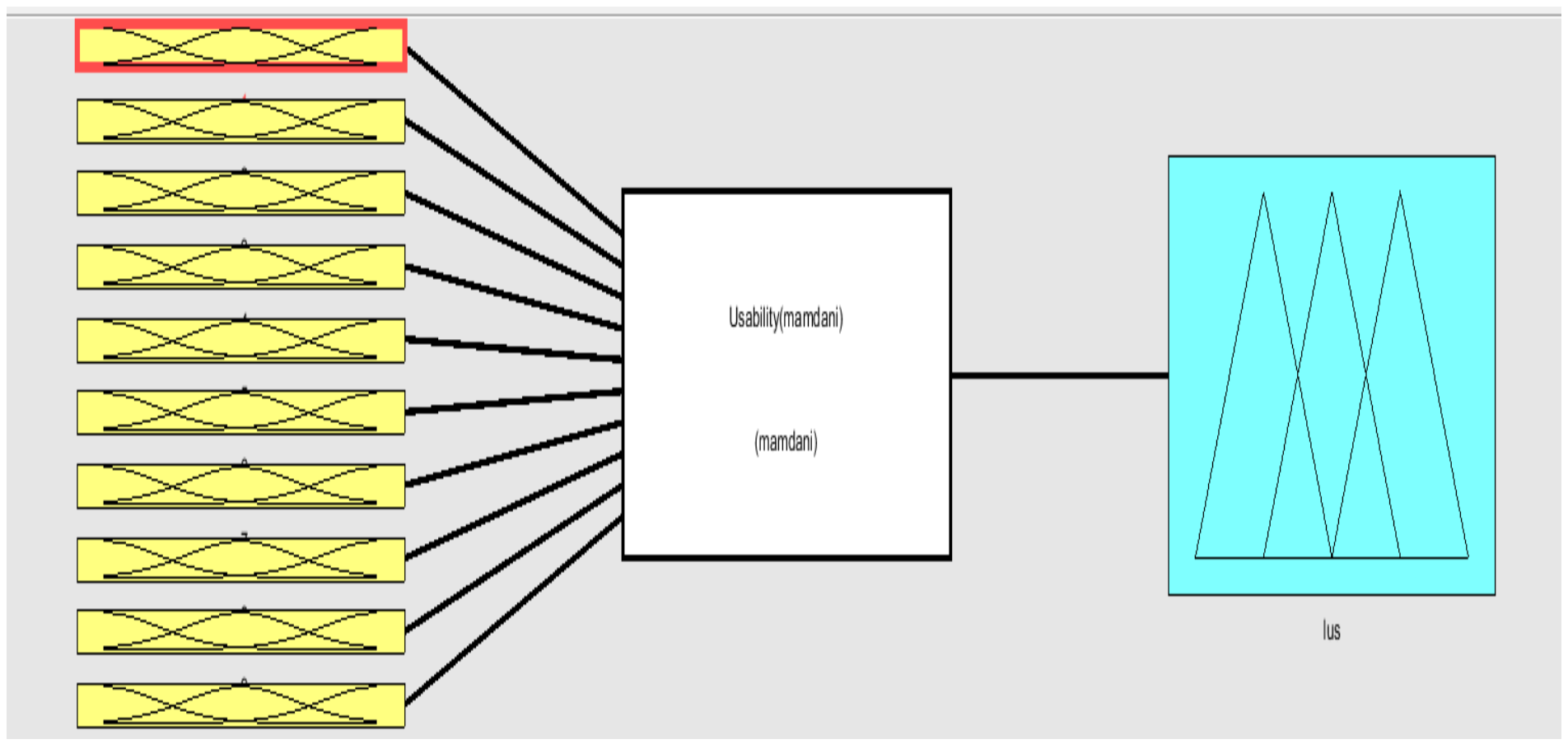

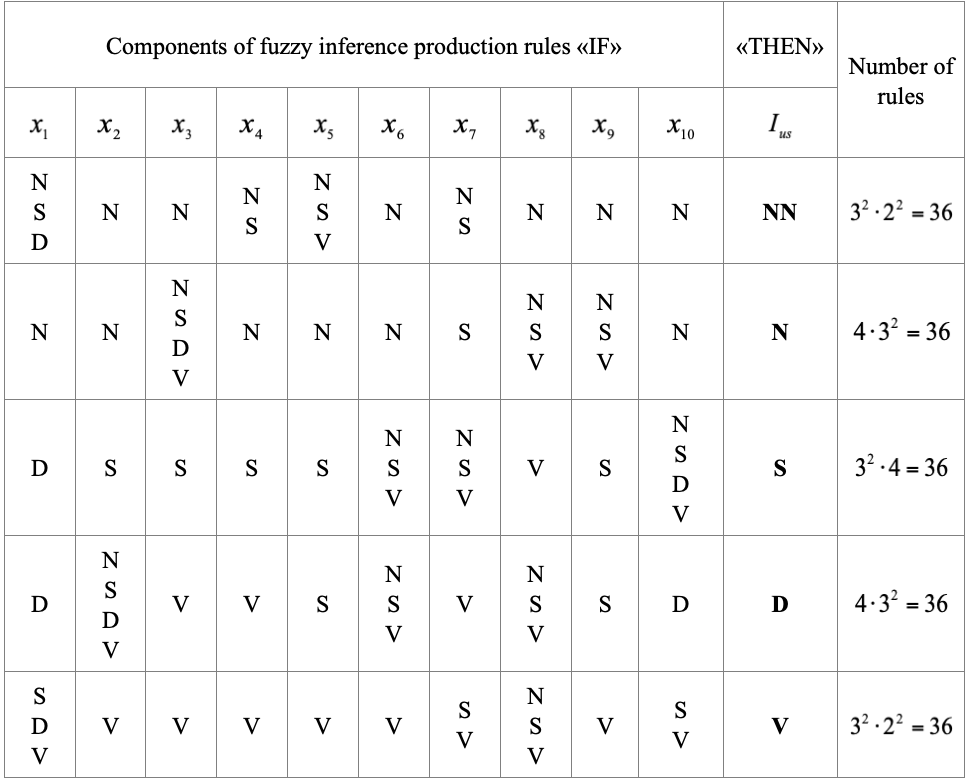

The fuzzy logic model uses Gaussian membership functions to represent input and output variables. These functions allow usability levels to be expressed as low, medium, sufficient, or high. The model was implemented using the Mamdani algorithm in MATLAB, which relies on rules such as:

“If loading speed is high and convenience is sufficient and accessibility is high, then overall usability is high.”

The output of the model is a single usability score, which represents the overall level of website usability. This score is expressed on a scale from extremely low to very high. The approach makes it possible to integrate multiple qualitative criteria into one comprehensive indicator of performance.

Model Implementation and Findings

The output usability score was modeled in MATLAB, where membership functions represent different levels of website performance. These functions illustrate how usability values range from very low to very high.

To connect multiple input criteria to a single usability score, the system used the Mamdani fuzzy logic inference method. This approach is visualized through a block diagram that shows how input variables—such as loading speed, accessibility, and interactivity—feed into the model.

A knowledge base of fuzzy rules was constructed to support decision-making. Each rule links input variable values to an overall usability level. Although theoretically thousands of rules could be generated, the study limited the system to 180 production rules. This balance ensured both precision and adaptability, allowing the model to respond flexibly to different data inputs.

Based on these rules, the system provided quantitative assessments of website usability.

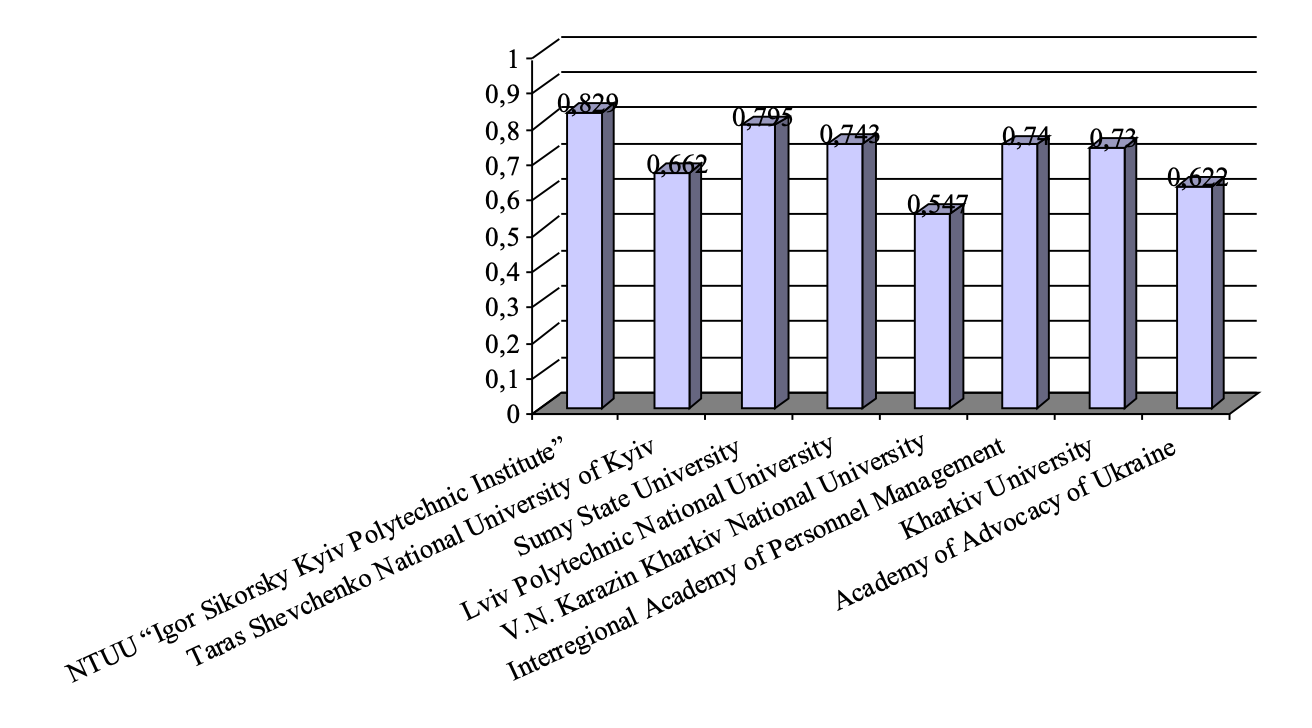

The results revealed three tiers of usability performance:

- High usability: NTUU “Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute”

- Sufficient usability: Sumy State University, Lviv Polytechnic National University, Interregional Academy of Personnel Management, Kharkiv University, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv

- Average usability: Academy of Advocacy of Ukraine, V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University

Conclusion

This study presents a fuzzy logic-based approach to assessing the usability of higher education websites. The model integrates ten usability criteria—loading speed, convenience, efficiency, relevance, accessibility, interactivity, cross-browser compatibility, lack of forced content, attractive design, and overall satisfaction. Together, these criteria provide a structured way to measure how user-friendly and effective university websites are.

The model relies on Gaussian membership functions for both input and output variables, chosen for their flexibility and simplicity. It was implemented in MATLAB using the Mamdani algorithm. To define input parameters, the study drew on a survey of 1170 stakeholders, including students and applicants, with results normalized against maximum possible scores.

A base of 180 fuzzy production rules was created, enabling the system to evaluate usability levels with precision. The results of the fuzzy inference model aligned with stakeholder survey data, confirming the accuracy of the approach. Findings showed that the website of NTUU “Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute” demonstrated high usability. Websites of Sumy State University, Lviv Polytechnic National University, Interregional Academy of Personnel Management, Kharkiv University, and Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv were found to have a sufficient level. Meanwhile, the websites of the Academy of Advocacy of Ukraine and V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University ranked at an average level.

Looking ahead, future research should focus on developing continuous monitoring systems and expanding the knowledge base of usability assessments. Further refinement of the methodology will help reduce subjectivity and strengthen the scoring process, ensuring that higher education institutions can reliably measure and improve the usability of their websites.

This article is a summary of the scientific work published by Hanna Kucherova, Yuliia Honcharenko, Dmytro Ocheretin and Olha Bilska

The original source can be accessed via DOI 10.33111/nfmte.2021.119

.png)

.png)